|

| source |

We were delighted to find "Silk Thread Martyrs’ on the cover of what was for us a very special issue of "Textile". We'll talk about that issue a bit in another post. For now, we want to remind you of 'Silk Thread Martyrs’:

|

| source |

Some Archive Education officers based in London saw the exhibition at The Mosaic Rooms in 2011. Here's it's original press release :

"To mark London Fashion Week, the Mosaic Rooms will showcase a new collection by one of the most promising young designers to recently emerge from the Arab world, OmarJoseph Nasser-Khoury.

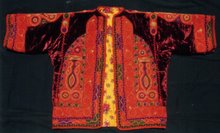

"Silk Thread Martyrs was conceptually inspired by the history and contemporary realities of the designer’s homeland, Palestine. Structurally and technically, the work draws inspiration from the traditional costumes and fabrics of that region and specifically the work of traditional Palestinian embroiderers, many of them refugees living in Lebanon or Jordan, who have maintained and developed the ancient skills of their lost homeland. Nasser-Khoury was inspired by the wonderful quality, rigorous detail and dedication of their work and, whilst creating his own collection, worked closely with them and with other local artisans and craftspeople. The result is a unique collection of outfits for men and women reflecting Palestine’s traditional and contemporary culture and its people: the farmer, the fighter, the martyr, the social worker, the refugee and, above all, the individual.

|

Silk Thread Martyrs

photography by Tarek Moukaddem

© Omarivs Ioseph Filivs Dinæ

|

"Silk Thread Martyrs creates a new, transformed and subverted look that explores gender, duty and social constraints. The collection features 22 individual garments, each unique in construction and design and made with the minimum use of machinery: embroidery, fabric, colouring and dyeing is carried out by hand, using natural materials such as indigo and tea. The design and production process of each garment will be explored through the exhibition.

"Omar Joseph Nasser-Khoury comments: “The omnipresence of death in daily life as a result of the Israeli Occupation has thrown society into a perpetual state of mourning. Rather than challenge that reality, the collection actually takes onboard the overbearing presence of loss in our lives and is thus a celebration of death. It flaunts the last thing that Palestinians still own: their doom.”We thought this curatorial premise intriguing and loved the exquisite images produced by photographer Tarek Moukaddem.

|

Silk Thread Martyrs

photography by Tarek Moukaddem

|

There's a great video of the exhibition opening in London. As always at art exhibition openings, hardly anyone is looking at the costumes. But we certainly were.

|

|

includes photography by Tarek Moukaddem

© Omarivs Ioseph Filivs Dinæ

|

We were very interested in getting a close to the works as possible. For us, it was all in the detail, whether it was a panel of embroidery or

the raw edging of a garment

or a thread under tension

We were inspired by everything we saw. We weren't at all surprised when we heard later the British Museum had acquired an item from the exhibition. We also weren't surprised when we later discovered Omar Joseph Nasser-Khoury's connection with INAASH in Lebanon. The Archive first began acquiring INAASH products in the mid 1980s. They were always stunning and innovative - at the time we were documenting their use of silk, pastel shades and beading. As their website states:

"From its inception Inaash has pursued a philosophy of excellence and creativity in design ... mindful of the crucial role of traditional needlework in Palestinian heritage [while] recognizing the outstanding aesthetic impact of this high quality craft when fused with contemporary sensibilities".This appealed to Omar Joseph Nasser-Khoury - this quote from an interview with Sue Jones in the issue of "Textile" at the top of this post:

"For the shirts and jackets, I worked with INAASH in Lebanon. I was very keen to work with them ever since I was introduced to their products, so I decided to do my college internship with them in Beirut; this was a year before I actually commenced working on “Silk Thread Martyrs.” I had to make a few phone calls and make use of a few great aunts to get through to the ladies there. I think it was the best educational experience I had during my time at college.

"INAASH is an important center of embroidery—it was started about forty years ago by a group of Lebanese and Palestinian women, who worked diligently on reintroducing embroidery work among the Palestinian refugees in Lebanon. What distinguishes them from almost all the other associations and women’s organizations is their attention to detail, color combinations, quality control, and use of fabrics. The irony is that these particularities were once part of the subconscious of the producers of Palestinian fashion and now they have become an extra advantage.

"The embroidery motifs are original INAASH arrangements that they were already producing on different items. My favorite two were the hjabat (amulets) and mafateeh njoum (star keys), which we had to alter slightly to adapt to my designs ... INAASH are famous for beading their embroidery, so I decided to carry that through in the work, but instead of the glass and plastic beads, I chose some copper, tin, and amber beads for the jackets..."

An INAASH product was very important in OmarJoseph Nasser-Khoury's own journey of discovery. Back to that interview with Sue Jones from "Textile":

"I live in Jerusalem. Growing up, I was usually making things; embroidery, however, was not something that interested or influenced me—neither my mother nor my grandmother embroidered. I did have an interest in making clothes though, simply because that made me feel I could have more control in terms of what I could wear, but it was just that. When a group of British fashion designers came to Palestine to look for potential and inspiration in traditional dress, I wondered why on earth there were no Palestinians with a similar interest. This, coupled with the experience of seeing a shawl embroidered by INAASH1 in Lebanon that my mother had bought on a trip to Beirut, made me decide to pursue an education in art and design. The decisive moment was when I saw the Palestinian costume collection at Birzeit University Museum. The small collection blew my mind—I had never imagined there was anything as profound or variant in terms of color, style, detail, nuance, and skill as I had seen.

In retrospect, I feel my decision was rather reactionary and narrow-minded. A lot of it was based on romance and nostalgia and this urge to “salvage and revive.” All the same, I do not think I would have been able to overcome this nonsense without having followed through my decision. Palestinians in Palestine and the shatat seem to be stuck in this place. I have been working on a project involving fashion design and dress and the participants with whom I was asked to share my experiences were very precious about the embroidery. There is this feeling that they are obliged to represent Palestine and the Cause through embroidery—which in turn has become sacrosanct, like a brand.

OmarJoseph Nasser-Khoury then raises several issues very close to our heart:

"You do still see women wearing embroidered dresses in Palestine. Originally and before the Nakba in 1948 and the Naksa in 1967, the majority of women who embroidered did it for their own personal consumption. Embroidery and dress were markers of wealth and social standing. All the same, as richer women became more globalized—and this is seen in towns like Bethlehem—they turned their attention toward European fashions. Now most of the women who embroider do it for others as a means of generating an income.

"Embroidery charities have been set up throughout Palestine and neighboring countries like Lebanon and Jordan to “empower” refugee women. I personally think this might have been the case forty years ago, but now, in addition to corrupting and bastardizing the art of embroidery, they do little besides maintaining a pathetic status quo.

"Most of what is produced in the charities is bought in sympathy and support for the Palestinians. The same goes for any creative work on that level. There is an inescapable dynamic of condescension at play here. I think there ought to be an informed and ruthless critique when it comes to the notion of cultural heritage and folklore. Especially when this heritage has become separable from our colloquial daily lives. It is problematic that the arena for Palestinian dress has now become the museum, private collections, coffee table books, and incompetent political discourse, rather than the bodies of Palestinians!

When the images taken by Tarek Moukaddem for the collection first became public, my aunt sent my mother an e-mail complaining that she saw little of “our beloved traditional costume” in the work. I cannot remember her true words, but she wrote something to that effect. I was bemused. Besides this, the overwhelming reception was laudatory and positive. What I found disconcerting was the automatic redemption of the work because of its Palestinianism. There was an obvious lack of critique when it came to fashion.

He elaborates on this point in an interview with This Week In Palestine:

"There’s been a very positive reaction to the fact that it’s Palestinian, but not enough fashion feedback, which worries me. To be honest I did project a political stance and people liked that, but my main concern is that the work carry the cause rather than the cause carry the work; therefore, I really concentrated on avoiding clichés so that the collection could be valued for its quality and worthiness of process in terms of thought and production.

Back to the This Week In Palestine interview:

"With the Nakba in 1948 came the death of many things, so this collection is mourning the martyrdom of everything that Palestine has lost since 1948; humans, heritage, style, freedom, costume, identity, the homeland, etc. The work is a rejection of this reality, it’s a protest that says, “Since we are not allowed to own anything, then we’ll own our death.” It’s basically giving the Occupation the V-sign.

It is also a celebration of Palestinian culture and an attempt at highlighting the breadth, variety, intricacy, and quality of the older Palestinian garments.

This was basically done through the employment of the “traditional” manual techniques of dressmaking, like stitching, embroidering, fabric manipulation, dying, etc. The point, however, was not to differentiate between the older and the contemporary in terms of traditional versus modern, rather to prove that Palestinian fashion is a continuous flow of innovation and reflection of reality.YES!!!! He continues:

"The aim was to create a collection that would initiate a discussion about the expression of identity through fashion. The garments are indeed physically wearable and comfortable, despite being extreme. However, they are garments that have been conceived to push the limits of what is usually perceived as typical Palestinian fashion, and to stimulate that discourse.

I’d like to make Palestinians more aware of the existing fashions we have and to take pride in them. During my internship in 2009 in Beirut with INAASH (Association for the Development of Palestinian Camps), a lady walked into their shop and noticed a detailed photo of a Galilee coat in Shelagh Weir’s book, Palestinian Costume; she assumed it was Indian and didn’t have the slightest clue that it was actually Palestinian. Many people, including Palestinians, don’t realise how rich Palestinian crafts are. The point is rather than sanctify these crafts they ought to be included and enjoyed in daily life. We ought to celebrate this part of our identity as we celebrate our cuisine, our music, and our literature - it’s quite pointless to limit these monumental garments merely to silly wedding celebrations."You can imagine how delighted we were when Omar Joseph Nasser-Khoury began curating exhibitions of Palestinian cultural heritage.

|

| source |

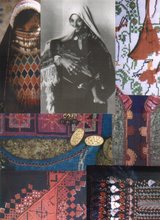

The first was Beyond Æsthetics (take a detailed look at it's brilliant poster above):

"an exhibition showcasing the Ethnographic and Art Museum’s Palestinian Costume and Tawfiq Canaan Amulet collections, curated on the basis of the visual symbolism and communication as seen in both collections. It aims to elaborate on how the potentials and possible attitudes, when exhibiting and studying ethnographic collections in a visual context, are virtually unlimited. With this approach, the Museum hopes to surpass the stiffness of nostalgia and conservatism which seem too often to confine and limit discourse and imagination when cultural heritage is in question. This exhibition comes as part of the 2011 series of events organized by the Museum aiming to bring the contemporary visual arts program closer to the University’s local community as well as to society as a whole, which in turn stresses on the importance of unconfined artistic practice and interaction."

This one sounds like a lot of fun and we are sorry we didn't see it. Next came Mvsevm: Seat of the Muse:

|

| source |

Again this was an interactive exhibition about breaking down the usual exhibit / audience / curator barriers, exploring:

“the dialogue between designers and museums and how the processes of inspiration, research, and creation interdependently develop. It aims to break down and deconstruct the traditional barriers that have been set up between the audience and the exhibited, inspiration and production, archive and gallery, by bringing all these elements into play within the exhibition space."Note the word "archive" there along with museum / gallery etc - this was for us like finally meeting someone in the curatorial world that shared our ideas:

"A core team of four individuals - the curator and three assistants - will carry out the project by compiling a body of research based on the manual techniques of construction found in items selected from the Palestinian Costume and Canaan Amulet ethnographic collections. The collated research and information will be used to build a collection of finalized fashion items, which in turn will reflect and investigate contemporaneity and practicality, and the aesthetic potential of these techniques.

"The physical openness of the space, coupled with the engaging setting, aims to actively involve the audience in the design, research, and production processes undertaken by the design team throughout the duration of the exhibition. Visitors will be able to see the team working in the space and interact with them in whatever capacity both see fit.

"Concentration will be on how museums and exhibited items can be used by creative individuals as a source of inspiration and information to generate knowledge. The project will look at the dynamic that develops between the exhibited item / artifact and the participants as viewers and creative individuals who will use the information to design and create a product throughout the period of the project.Next post we'll talk about the rest of the articles in that issue of Textile. Meanwhile, for now we look forward to Omar Joseph Nasser-Khoury's future endeavours with much interest :)

"The research process, design development, product realization, and audience interaction that take place at the museum will create a workshop space that, in turn, becomes and generates the exhibition itself. This means that the process, information, conclusions, and ideas gathered and developed throughout the project by the exhibition team and the audience are approached and exhibited, as one would approach works of art or ethnographic items - almost as an interactive installation. These will be constantly developing throughout the exhibition and changed in such a way that for an individual viewer the space will never look the same on two different visits...."

More info:

- The Mosaic Rooms - Silk Thread Martyrs press release OmarJoseph Nasser-Khoury (OMARIVS IOSEPH FILIVS DINÆ) 18 February – 9 March 2011

- Silk Thread Martyrs film - Neville Rigby

- This Week in Palestine - What a Beautiful Mourning June 2012

- Sue Jones “Silk Thread Martyrs”: Palestinian Embroidery in Textile Volume 11, Issue 2, pages 196-201

- Beyond Æsthetics BZU

No comments:

Post a Comment