|

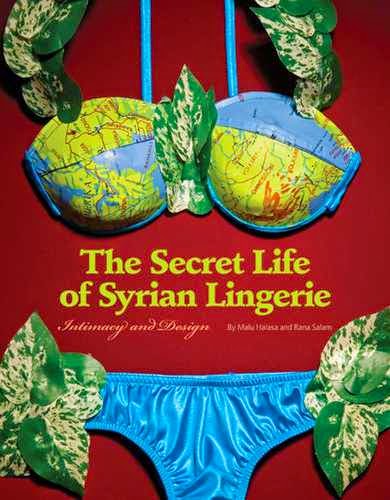

| “Salma” by Sliman Mansour (1988) published by Roots Palestine Poster Project Archives website source |

We were absolutely delighted to hear that the Palestine Poster Project Archives has been accepted for formal review by the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization’s Memory of the World program. The UNESCO program’s International Register inscribes library and archival holdings of “world significance and outstanding universal value.” The nomination form states:

"Posters in the Liberation Graphics Collection representing a key era in the evolution and maturation of Palestine poster art, providing primary documentary data on the contemporary history of Palestine and serving as an extraordinary source of inspiration for artists from a diverse range of geographic locales, political affiliations, nationalities, and aesthetic perspectives. The Palestine poster genre is unique in world art and a much overlooked feature of Palestinian cultural heritage "It is, indeed. As Dan Walsh, curator and owner of the Archives, says in an interview on the Mondoweiss website:

"these posters ... create a rich and textured portrait of Palestine that’s very different from the caustic and superficial stereotypes with which Palestinians were burdened subsequent to the Nakba. In these works of art we see keys and kaffiyehs, oranges and olives, horses and doves, poetry and embroidery, all mobilized to tell a story. These and other symbols, icons, and traditions of Palestinian identity are celebrated, preserved, and legitimated in the posters.

"So the posters are a real teaching tool. Viewed collectively, they enable Palestinians to learn more about their own history and for non-Palestinians to undo the hasbara that has mis-educated them. It’s a source for national pride"We're so pleased to see this nomination. The Palestine Poster Project Archives and the Palestine Costume Archive share many things. Both archives came into being after academic research revealed the need. Both are staffed by volunteers. Both operate with severely limited resources. Both are committed to education. Both acquire specific forms of Palestinian cultural heritage. Both of us have collection / research areas which overlap - we both acquires posters featuring traditional Palestinian costume and embroidery iconography. Our own archive has a large works on paper collection, with a small but significant poster collection that always features in our traveling exhibitions, although sadly we lost about half our poster collection when our traveling exhibition "Symbolic Defiance: Palestinian costumes and embroideries since 1948" was "mislaid" at LAX on it's way to MESA, after being displayed at WOCMES.

We also like that the Palestine Poster Project Archives shares our frustration with Palestinian cultural material being mislabeled in archives and libraries and museums - Dr Walsh mentions this in the You Tube video below, which was a talk he gave at the Palestine Fund:

We know how hard everyone at the Palestine Poster Project Archives works, and we think it would be wonderful if that hard and very important work was acknowledged in this way :)

Here's the rest of that interview, published on August 16, 2014:

In early August, the nomination of a major collection of posters from the Palestine Poster Project Archives was accepted for formal review by the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization’s Memory of the World program. The UNESCO program’s International Register inscribes library and archival holdings of “world significance and outstanding universal value.”

The nominated work, the Liberation Graphics Collection of Palestine Posters, is the first documentary heritage resource ever nominated by the state of Palestine for inscription to the Memory of the World. The review process takes about a year to complete. If inscribed, the Palestine posters will join a register that includes the Bayeux Tapestry, the Book of Kells, the Phoenician Alphabet, the Gutenberg Bible, Karl Marx’s personally annotated manuscript of Das Kapital, and hundreds of other historically significant documents.

Aside from the prospect of inscription into this prestigious register, the nomination itself is a watershed event for Palestinian art, culture, and history. Its significance is addressed in the following exchange between Dan Walsh, curator and owner of the Archives, and Catherine Baker, a member of the Archives’ advisory board.

CB: Dan, describe the collection that has been nominated.

DW: The Palestine Poster Project Archives includes paper and digital images of almost 10,000 Palestine posters created by more than 1,900 artists from 72 countries. It’s growing by the day, both through acquisition of older posters and the addition of newly created works. UNESCO’s Memory of the World only includes defined and complete resources, so what was proposed for inscription is our core collection. This is a body of 1,700 posters published from the mid-sixties through the mid-nineties. They were produced during a key period in Palestinian history commencing around the time of the Six-Day War of 1967 and the 1968 battle of Al Karameh and continuing through the first intifada. The posters reveal how Palestinians organized and asserted themselves in response to the loss of land and the resulting displacement and diaspora.

CB: Who made these posters?

DW: Hundreds of Palestinian artists are represented. Some produced their work at locations within Palestine and others contributed from points around the globe. Palestinian artists whose names Mondoweiss readers might recognize include Ismail Shammout, Kamal Boullata, and Sliman Mansour, but there are many others. The posters also represent a wide range of Palestinian publishers, from the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine to lesser known groups such as the General Union of Palestinian Plastic Artistsand, of course, the artists as publishers themselves.

A good many of the posters were created in solidarity by non-Palestinians. To name a few: Marc Rudin from Switzerland, whose early solidarity with Palestinians earned him the honorific Jihad Mansour; the Italian comics illustrator Elfo; and the Italian set designer Elizabetta Carboni. There are many international artists who created Palestine solidarity posters in their early years and have subsequently enjoyed prominent careers in the arts. A number of the international posters in the Liberation Graphics Collection were self-published by the artists, others were published specifically for exhibits such as Palestine: A Homeland Denied, and a substantial portion were published by organizations outside of Palestine; as one example, the Organization of Solidarity with the Peoples of Africa, Asia and Latin America.

CB: What topics do these posters address?

DW: This particular collection includes many about armed struggle, but other themes emerge as well. A 1982 poster quoting Yasser Arafat says: “This revolution is not merely a gun, but also a scalpel of a surgeon, a brush of an artist, a pen of a writer, a plough of a farmer, an axe of a worker.” These posters reflect that society-wide commitment to the revolution. Some are about a particular individual or group of Palestinians, and some are about events such as music festivals or cultural traditions such as sculpture and film. We’ve got posters on the theme of return, literacy, voting, children’s theatre, refugehood, you name it. The joys and the challenges of Palestinian life are all represented here.

CB: In a nutshell, what’s the big deal about this nomination?

DW: Apart from the possibility of actual inscription in UNESCO’s Memory of the World register—which we hope will occur following the review process—the nomination itself brings world attention to a unique genre of posters that heretofore has been essentially unrecognized.

CB: What do you mean by that?

DW: Typically, posters related to Palestine have been archived by libraries and museums under all sorts of rubrics depending on who made them or where they were made. They’ve been catalogued under various terms such as Muslim, Arab, Middle East, Jewish, Israeli, Holy Land, Levant, and so on. This means that related posters were not readily available for unified analysis. We posted a definition of the Palestine poster at the Archives web site, and we included all posters that met that definition. When we did that, what emerged is a unique genre of tremendous breadth and scope. It’s a goldmine for artists, historians, and academics. There is simply nothing else out there like that in the poster tradition.

CB: You’ve twice now called the Palestine poster a “unique genre.” On what grounds do you make this claim?

DW: First of all, it’s the only political poster genre to make it from the street to the Internet. The other major poster genres of the mid-twentieth century— such as the posters of the Spanish Civil War, revolutionary Cuba, Nicaragua’s Sandinista movement, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, the People’s Republic of China, Zionist colonialism—they’ve all faded away. Only the Palestine poster genre endured to the twenty-first century, seamlessly made the transition to the digital age, and continues to flourish.

Another factor that makes the Palestine poster genre unique is the degree to which it has been suppressed, censored, banned, and forced underground. At the web site we have a whole special collection dedicated to this topic.

But perhaps what is most unique about the Palestine poster genre is that it has survived virtually intact. After all, what is a poster but a piece of paper that’s plastered on a building, handed out at a concert, or taped to a dorm wall? It’s not meant to last; it’s ephemeral. But those 1,700 posters in the Liberation Graphics Collection were preserved because people kept them. People around the world participated in a spontaneous expression of salvage anthropology. They stored posters in their attic or in a roll under their bed or in the back of their artist’s studio. And eventually they contributed those posters to the Palestine Poster Project Archives. And they’re still doing that. Every month, it seems, somebody contacts me about some posters they picked up back when they were traveling or produced themselves a decade or four ago. And so since 2005, when we launched the web site, we’ve seen this narrative emerge. It’s like a documentary film in the making. Collectively, the people of Palestine and their friends are fleshing out an authentic history of contemporary Palestine.

CB: Now I have to ask you to explain to Mondoweiss readers what you mean by “authentic history.”

DW: The narrative presented by the Palestine posters is authentic in the sense that it is by, for and about Palestine and the Palestinians. No editors, no censors. Each poster reveals the attitudes, aspirations, and actions present at the moment of the poster’s creation. It’s unfiltered and it’s unrevised by later events. Collectively these posters carry incredibly useful primary data on Palestinian political, military, cultural, and social history.

I need to say here that, with some incredibly hardworking volunteers, we have been able to build a super-powerful Drupal site that is searchable six ways from Sunday. Academics enthuse over the capacity of the web site. I expect to see some impressive research coming out in the next few years based on this resource.

CB: Talk to me more about the role of artists in forming the history of contemporary Palestine.

DW: We’ve heard from the politicians, the journalists, and the diplomats and the academics—all the professionals in the so-called peace process industry. This genre elevates the voices of the artists. It allows us to hear people speaking directly to people. You look at these posters and you walk away with a completely different take on what Palestine is and what it means to be Palestinian, compared with what you get from talking heads through the news media. The great titles resonate: this quality is not something that can be fabricated, purchased, or faked.

CB: Aesthetically, what excites you most about the posters in the nominated collection?

To their credit, the early Palestinian political leadership never sought to centrally control either the internal or international production of posters. As a result, artists from around the world had the freedom to combine their own graphic styles and iconography with those of contemporary Palestine. The result is an astounding cross-fertilization. A good example is the 1979 poster, “Palestine: A Homeland Denied,” in which Thomas Kruze fuses the Danish woodcut style with the Palestinian iconography of white horse, dove, and embroidery. The posters also reveal how much the Palestinian cause has been taken to heart by political movements around the world. We see the joining of causes in, for example, Lazaro Abreu’s 1971 Cuban poster expressing solidarity with Syria, in which the flag of Palestine is included almost pro forma. And we see solidarity reaching out in the other direction, in such posters as Solidarity With Students, People, and Youth of Vietnam.

That’s a poster created by Hosni Radwan and published by the General Union of Palestinian Students.

There’s one other thing I really love about these posters. It’s the remixing—the borrowing of iconography to make a new statement. Take for example the 1988 poster “From the Launching to the Uprising An Incredible Journey.” It was created by an unknown artist and published by an American artists’ collective called Roots. The poster features a photograph of a woman waving the Palestinian flag. That same year, artist Rene Castro re-mixed the image as a silkscreen for the poster, “In Celebration of the State of Palestine. ”

CB: What’s the end goal with the UNESCO Memory of the World nomination?

DW: As you well know, the Palestine Poster Project Archives is supported by nothing more than a collection of volunteers, both Palestinian and non-Palestinian. We’re doing the best we can with limited resources, but these posters need to be prepared for eventual acquisition by a Palestinian national institution capable of maintaining them in perpetuity. Ideally, this would be in Palestine itself. The Memory of the World nomination will hopefully help raise public consciousness and generate resources that will enable us to properly conserve these posters.

But sharing these posters with the world has another benefit, because they create a rich and textured portrait of Palestine that’s very different from the caustic and superficial stereotypes with which Palestinians were burdened subsequent to the Nakba. In these works of art we see keys and kaffiyehs, oranges and olives, horses and doves, poetry and embroidery, all mobilized to tell a story. These and other symbols, icons, and traditions of Palestinian identity are celebrated, preserved, and legitimated in the posters.

So the posters are a real teaching tool. Viewed collectively, they enable Palestinians to learn more about their own history and for non-Palestinians to undo the hasbara that has mis-educated them. It’s a source for national pride— the Palestinians’ gift to the world, really. In an article I wrote a few years ago, I called the Palestine poster genre the “visual equivalent of jazz.”

CB: This is the first-ever nomination of a documentary heritage by the state of Palestine to UNESCO’s Memory of the World program. What other UNESCO programs recognize Palestinian art, culture and heritage?

DW: The poster nomination as a documentary heritage comes on the heels of two successful inscriptions of geographic sites by Palestine to UNESCO’s World Heritage List. The first was Church of the Nativity and the Pilgrimage Route in Bethlehem, inscribed in 2012; this was the first bid by Palestine after joining UNESCO. And in June of this year, the cultural landscape of southern Jerusalem, Battir, was also inscribed on the World Heritage List, after an emergency nomination that Palestine submitted in face of the threat posed by extension of the separation wall. All this UNESCO activity is raising the cultural prestige of Palestine, which is a welcome development.More Info:

- Palestine Poster Project Archives

- UNESCO's Memory of the World program

- Wiki - Palestine Poster Project Archives

- Leah Caldwell "The Palestine Poster Project: A Virtual Memory of Struggle and the Everyday". Al-Akhbar English 6 Dec 2011

- Philip Kennicott “Poster Art, Painted with a Palestinian Perspective,” The Washington Post

- Maureen Clare Murphy - “Review: Poster Art of the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict,” The Electronic Intifada Jan 2004

- Dan Walsh - thesis: "The Palestine Poster Project Archives: Origins, Evolution, and Potential".